In February this year, First Lady Michelle Obama announced what she called a “very ambitious” program to end childhood obesity. This nationwide campaign, called “Let’s Move,” calls for initiatives that target parents and schools, and that provides information about nutrition and exercise, improving school food quality and making healthy foods affordable and accessible for families. This program also focuses on physical education. While these initiatives are commendable, how bad is the childhood obesity problem and are these initiatives worth pursuing?

The following statistics are divided into categories with numerous links to information that back the numbers, including links provided through each image. All information is gathered from government resources and scientific surveys and tests to lend credence to this serious issue.

The Facts

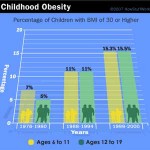

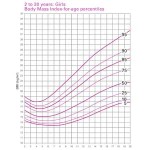

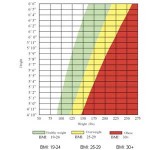

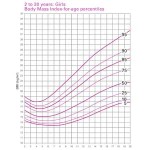

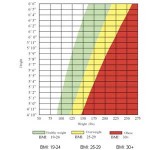

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), childhood obesity has more than tripled in the past 30 years. The prevalence of obesity among children aged 6 to 11 years increased from 6.5 percent in 1980 to 19.6 percent in 2008. This chart shows how the CDC measures obesity by Body Mass Index (BMI). A BMI score of 30 or more in a child is a serious health risk.

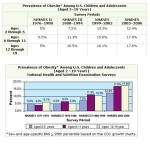

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), childhood obesity has more than tripled in the past 30 years. The prevalence of obesity among children aged 6 to 11 years increased from 6.5 percent in 1980 to 19.6 percent in 2008. This chart shows how the CDC measures obesity by Body Mass Index (BMI). A BMI score of 30 or more in a child is a serious health risk. Data from NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) shows that among preschool-aged children, aged 2–5 years, the prevalence of obesity increased from 5.0 percent to 12.4 percent; among school-aged children, aged 6–11 years, the prevalence of obesity increased from 4.0 percent to 17.0 percent, and; among school-aged adolescents, aged 12–19 years, the prevalence of obesity increased from 6.1 percent to 17.6 percent.

Data from NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) shows that among preschool-aged children, aged 2–5 years, the prevalence of obesity increased from 5.0 percent to 12.4 percent; among school-aged children, aged 6–11 years, the prevalence of obesity increased from 4.0 percent to 17.0 percent, and; among school-aged adolescents, aged 12–19 years, the prevalence of obesity increased from 6.1 percent to 17.6 percent. Although obesity has increased for all children and adolescents over time, NHANES data indicate disparities among racial/ethnic groups. The prevalence rate of obesity was higher among adolescent Mexican-American boys (22.1 percent) and than among non-Hispanic white boys (17.3 percent) and black boys (18.5 percent).

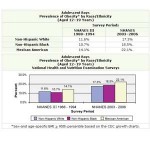

Although obesity has increased for all children and adolescents over time, NHANES data indicate disparities among racial/ethnic groups. The prevalence rate of obesity was higher among adolescent Mexican-American boys (22.1 percent) and than among non-Hispanic white boys (17.3 percent) and black boys (18.5 percent). The most recent NHANES data (2003–2006) showed that for girls, aged 12–19 years, non-Hispanic black girls had the highest prevalence of obesity (27.7 percent) compared to that of non-Hispanic white (14.5 percent) and Mexican American girls (19.9 percent).

The most recent NHANES data (2003–2006) showed that for girls, aged 12–19 years, non-Hispanic black girls had the highest prevalence of obesity (27.7 percent) compared to that of non-Hispanic white (14.5 percent) and Mexican American girls (19.9 percent). If both parents are overweight, the child’s likelihood of being overweight increases by 60-80 percent. With two lean parents, the child’s capacity for being overweight increases only by nine percent. But, an overweight adolescent has a 70 percent chance of becoming an overweight or obese adult.

If both parents are overweight, the child’s likelihood of being overweight increases by 60-80 percent. With two lean parents, the child’s capacity for being overweight increases only by nine percent. But, an overweight adolescent has a 70 percent chance of becoming an overweight or obese adult. Looking forward based upon these statistics about overweight or obese children becoming overweight or obese adults, Mississippi children may need to work harder than most children across the nation to reduce childhood obesity according to this map produced by CalorieLab. A further eye-opener is the map that shows how thin Canadians are in comparison to U.S. citizens.

Looking forward based upon these statistics about overweight or obese children becoming overweight or obese adults, Mississippi children may need to work harder than most children across the nation to reduce childhood obesity according to this map produced by CalorieLab. A further eye-opener is the map that shows how thin Canadians are in comparison to U.S. citizens.

Childhood Obesity and Physical Consequences

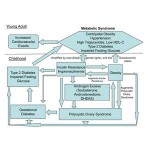

When overweight children become overweight adults, they carry into their adulthood long-term morbidity and mortality. One of these problems includes heart disease, or a strong adverse impact on multiple cardiovascular risk factors, requiring primary prevention early in life.

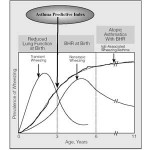

When overweight children become overweight adults, they carry into their adulthood long-term morbidity and mortality. One of these problems includes heart disease, or a strong adverse impact on multiple cardiovascular risk factors, requiring primary prevention early in life. Childhood obesity statistics also predict a prevalence of type 2 diabetes, commonly known as adult-onset diabetes. In 2005, the CDC estimated that 176,500 people aged 20 years or younger have been given a diagnosis of diabetes. The disease disproportionately affects children of American Indian, African-American, Mexican American, and Pacific Islander ethnic backgrounds.

Childhood obesity statistics also predict a prevalence of type 2 diabetes, commonly known as adult-onset diabetes. In 2005, the CDC estimated that 176,500 people aged 20 years or younger have been given a diagnosis of diabetes. The disease disproportionately affects children of American Indian, African-American, Mexican American, and Pacific Islander ethnic backgrounds. Overweight children can develop arthritis, the number one cause of chronic disability in the U.S. In a recent study, 135 overweight children complained of back pain, followed closely by foot, knee, and hip pain. Symptoms of arthritis can improve with weight loss. According to the CDC, an estimated 294,000 children under age 18 have some form of arthritis or rheumatic condition; this represents approximately 1 in every 250 children.

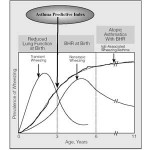

Overweight children can develop arthritis, the number one cause of chronic disability in the U.S. In a recent study, 135 overweight children complained of back pain, followed closely by foot, knee, and hip pain. Symptoms of arthritis can improve with weight loss. According to the CDC, an estimated 294,000 children under age 18 have some form of arthritis or rheumatic condition; this represents approximately 1 in every 250 children. Overweight and obesity are associated with increased risks of gall bladder disease, incontinence, increased surgical risk, and depression. Other health concerns include orthopedic problems and sleep apnea. Obesity also is associated with a higher prevalence of asthma.

Overweight and obesity are associated with increased risks of gall bladder disease, incontinence, increased surgical risk, and depression. Other health concerns include orthopedic problems and sleep apnea. Obesity also is associated with a higher prevalence of asthma. The most immediate consequence of overweight, as perceived by children themselves, is social discrimination, a problem that may keep some overweight kids from exercising with other children and that can produce psychological effects that can last a lifetime.

The most immediate consequence of overweight, as perceived by children themselves, is social discrimination, a problem that may keep some overweight kids from exercising with other children and that can produce psychological effects that can last a lifetime. Some reports have questioned whether childhood obesity is a form of parental abuse, assuming the child is not suffering from a genetic obesity disease such as a thyroid issue. Further, these inquiries probe the question whether parents should be held liable if the child dies from an obesity-related disease.

Some reports have questioned whether childhood obesity is a form of parental abuse, assuming the child is not suffering from a genetic obesity disease such as a thyroid issue. Further, these inquiries probe the question whether parents should be held liable if the child dies from an obesity-related disease. According to the Surgeon General’s office, an estimated 300,000 deaths per year may be attributable to obesity. The risk of death rises with increasing weight, and even moderate weight excess increases the risk of death. In sum, individuals who are BMI > 30 have a 50 – 100 percent increased risk of premature death from all causes, compared to individuals with a healthy weight.

According to the Surgeon General’s office, an estimated 300,000 deaths per year may be attributable to obesity. The risk of death rises with increasing weight, and even moderate weight excess increases the risk of death. In sum, individuals who are BMI > 30 have a 50 – 100 percent increased risk of premature death from all causes, compared to individuals with a healthy weight.

Control and Prevention

The U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service developed a new food pyramid in 2005, with a newer version to be published in 2010. While this pyramid shows a healthy balance of food, critics state that it also shows a large portion of each food; therefore, this lack of food portion size can lead to confusion and also may lead to overeating and obesity.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service developed a new food pyramid in 2005, with a newer version to be published in 2010. While this pyramid shows a healthy balance of food, critics state that it also shows a large portion of each food; therefore, this lack of food portion size can lead to confusion and also may lead to overeating and obesity. Despite the issues with the food pyramid, My Pyramid for Kids includes tips for families and parents that offer solutions to many nutrition and health issues. Included in this portal is a poster that contains physical activity tips for kids and for families.

Despite the issues with the food pyramid, My Pyramid for Kids includes tips for families and parents that offer solutions to many nutrition and health issues. Included in this portal is a poster that contains physical activity tips for kids and for families. Overweight and obesity can result from an imbalance involving excessive calorie consumption and/or inadequate physical activity. It is recommended that Americans accumulate at least 30 minutes (adults) or 60 minutes (children) of moderate physical activity most days of the week. More may be needed to prevent weight gain, to lose weight, or to maintain weight loss.

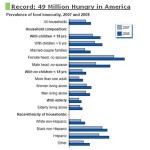

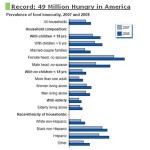

Overweight and obesity can result from an imbalance involving excessive calorie consumption and/or inadequate physical activity. It is recommended that Americans accumulate at least 30 minutes (adults) or 60 minutes (children) of moderate physical activity most days of the week. More may be needed to prevent weight gain, to lose weight, or to maintain weight loss. Food insecurity may play a part in obesity, as poor families may choose less expensive foods which may be less nutritious. The USDA released a report [PDF] about ‘food insecurity,’ an issue that shows an increase in numbers from 36 million people in 2007 to 49 million in 2008. This increase in 13 million individuals who had food shortages in the household may correlate to childhood obesity.

Food insecurity may play a part in obesity, as poor families may choose less expensive foods which may be less nutritious. The USDA released a report [PDF] about ‘food insecurity,’ an issue that shows an increase in numbers from 36 million people in 2007 to 49 million in 2008. This increase in 13 million individuals who had food shortages in the household may correlate to childhood obesity. Learn about the possibilities for healthy food in your area. The USDA has created a “Food Environment Atlas,” which is basically a Google Map that users can manipulate to find out all kinds of things about America’s food system at both macro and micro levels, based on government data that can be mixed and matched. You can learn about fast-food concentrations, and you can see areas where a lot of poor people live and where the nearest grocery store is more than a mile away.

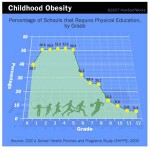

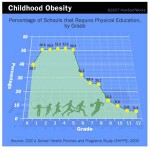

Learn about the possibilities for healthy food in your area. The USDA has created a “Food Environment Atlas,” which is basically a Google Map that users can manipulate to find out all kinds of things about America’s food system at both macro and micro levels, based on government data that can be mixed and matched. You can learn about fast-food concentrations, and you can see areas where a lot of poor people live and where the nearest grocery store is more than a mile away. More schools have cut back on physical education or even recess from the school day. Time and resources that used to be spent on physical education is now being taken up complying with the strict standards of the No Child Left Behind Act. Don’t wait for your school to change its ways. You are in charge of your own nutrition and your child’s nutrition at school.

More schools have cut back on physical education or even recess from the school day. Time and resources that used to be spent on physical education is now being taken up complying with the strict standards of the No Child Left Behind Act. Don’t wait for your school to change its ways. You are in charge of your own nutrition and your child’s nutrition at school. Learn about what you can do from the Office of the Surgeon General. Additionally, if you want to motivate your child, one way to do this is to show your child what he/she will look like in the future if weight is not lost.

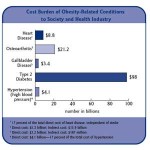

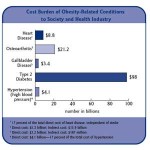

Learn about what you can do from the Office of the Surgeon General. Additionally, if you want to motivate your child, one way to do this is to show your child what he/she will look like in the future if weight is not lost. Learn about the cost of childhood obesity, and learn how this information can be used in your school or neighborhood to help reduce the crisis of childhood obesity. At the individual level, obesity is associated with health care costs that average about 30 percent above those for normal weight individuals. But, all taxpayers pay for the costs of obesity.

Learn about the cost of childhood obesity, and learn how this information can be used in your school or neighborhood to help reduce the crisis of childhood obesity. At the individual level, obesity is associated with health care costs that average about 30 percent above those for normal weight individuals. But, all taxpayers pay for the costs of obesity. You can ensure that schools provide healthful foods and beverages on school campuses and at school events by following the advice offered by the Surgeon General. One idea is to go to your child’s school during lunchtime to observe whether the school is abiding by USDA regulations that prohibit serving foods of minimal nutritional value.

You can ensure that schools provide healthful foods and beverages on school campuses and at school events by following the advice offered by the Surgeon General. One idea is to go to your child’s school during lunchtime to observe whether the school is abiding by USDA regulations that prohibit serving foods of minimal nutritional value. Another way to help fight childhood obesity is to adopt policies specifying that all foods and beverages available at school contribute toward eating patterns that are consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. For example, Senator Padilla in California introduced a bill in February this year that intends to bar sales of sugar-sweetened sports drinks at that state’s public schools during school hours.

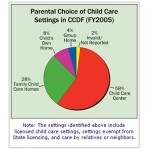

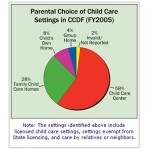

Another way to help fight childhood obesity is to adopt policies specifying that all foods and beverages available at school contribute toward eating patterns that are consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. For example, Senator Padilla in California introduced a bill in February this year that intends to bar sales of sugar-sweetened sports drinks at that state’s public schools during school hours. After-school programming is an ideal setting for promoting healthy lifestyles among school-age children. According to this graphic provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in 2005 a majority of after-school care was provided by child care centers and family child care centers. These programs, however, often lack monetary support to develop programs and to hire professionals to help build and activate programs.

After-school programming is an ideal setting for promoting healthy lifestyles among school-age children. According to this graphic provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in 2005 a majority of after-school care was provided by child care centers and family child care centers. These programs, however, often lack monetary support to develop programs and to hire professionals to help build and activate programs. The Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) provides federal resources for child care that support both direct services and quality enhancements. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Child Care Bureau awards CCDF grants to states, territories, and tribes, and the majority of CCDF dollars are used to provide subsidies to eligible low-income children under age 13. Use resources such as these to help build community programs that can help you, your child and your neighbors.

The Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) provides federal resources for child care that support both direct services and quality enhancements. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Child Care Bureau awards CCDF grants to states, territories, and tribes, and the majority of CCDF dollars are used to provide subsidies to eligible low-income children under age 13. Use resources such as these to help build community programs that can help you, your child and your neighbors.